Invaluable monumental artworks, created by a group of Ukrainian monumentalists led by Alla Horska, a dissident artist and one of the Sixtiers movement’s founders. These panels incorporated elements of Ukrainian folk tradition, contemporary world trends, and Soviet art.

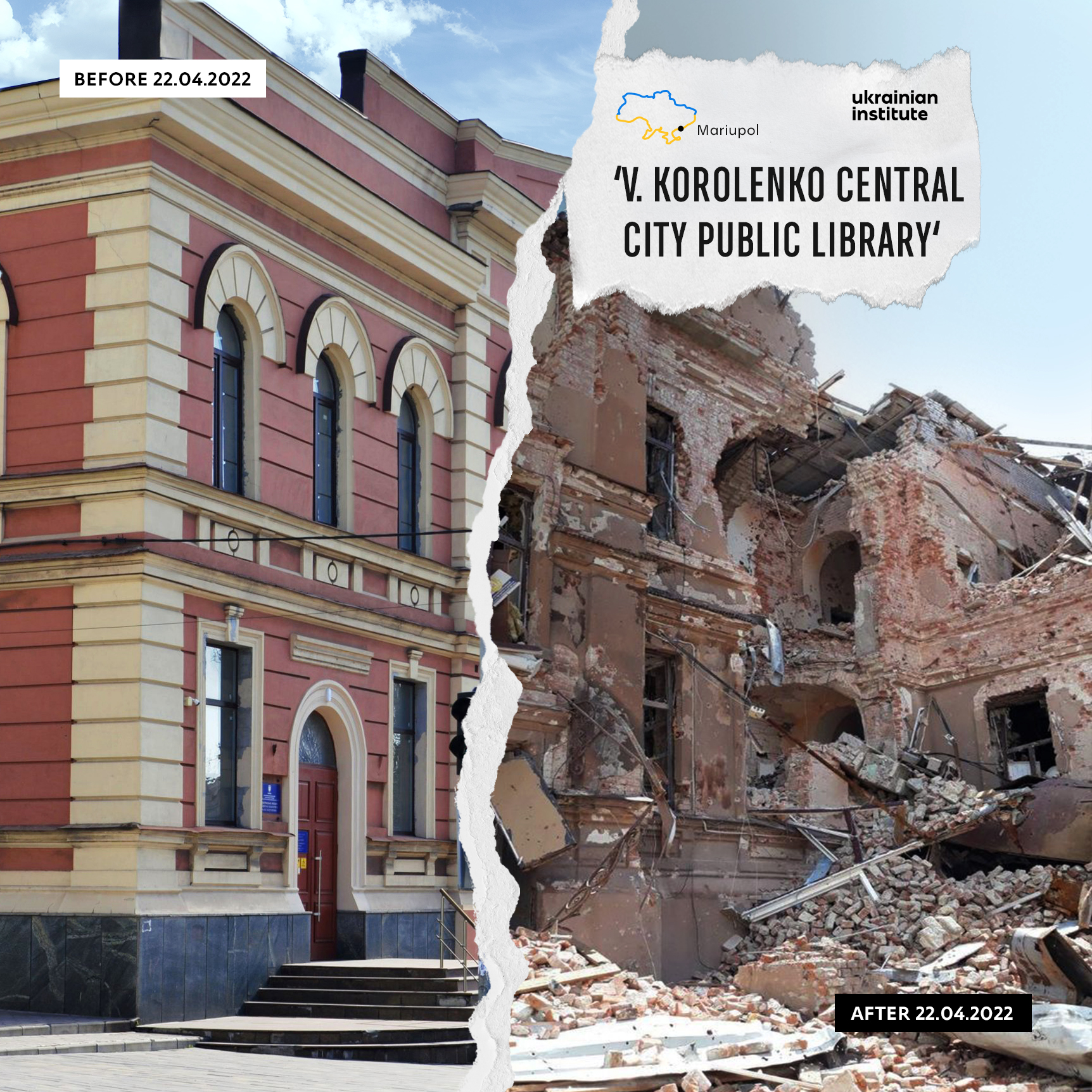

Mariupol, a Ukrainian port city on the coast of the Azov Sea, is rich in objects that are of high architectural and artistic value. Among them is one of the biggest and most diverse collections of Ukrainian monumental mosaics, created between the 1960s and 1980s by prominent masters of this style.

Monumental art is extremely vulnerable due to its highly visible exposure to the public since it is always present in public space. For this reason, stories about particular works of art in this style are often unusual and even dramatic.

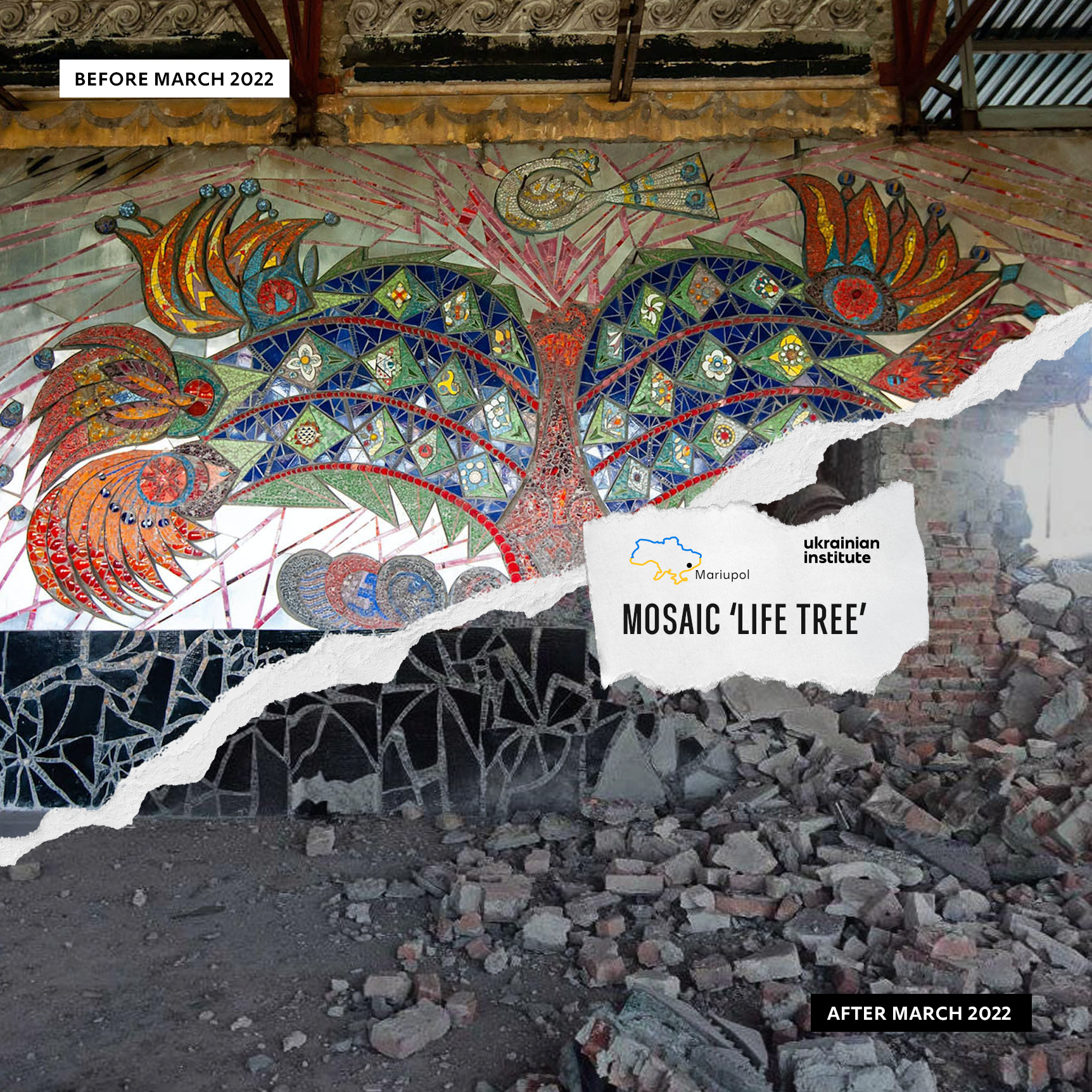

The year 2008 brought an outstanding artistic discovery to Ukraine. During a major renovation of the Mariupol restaurant ‘Ukraine’, which was built before WWII, two mosaic panels were found behind one of its walls. These panels were created by a group of Ukrainian monumentalists led by Alla Horska, a dissident artist and one of the Sixtiers movement’s founders.

In 1967, Alla Horska, joined by a group of co-author artists including Viktor Zaretskyi, Halyna Zubchenko, Borys Plaksii, Hryhorii Pryshedko, Vasyl Prakhnin, and Nadiia Svitlychna, arrived in Mariupol. In less than two months, they created the ‘Tree of Life’ and ‘Kestrel’ mosaics in the ‘Ukraine’ restaurant. Mariupol researchers of monumental art Ivan Stanislavskyi and Oleksandra Chernova call them the most valuable mosaics in the city.

The artists sought to combine Ukrainian folk tradition, contemporary world trends, and Soviet art in these panels. Hence, they used non-standard materials such as slag ceramics and metal. The ‘Tree of Life’ shone due to sheet aluminium, and the artists even used fragments of aluminium spoons in the ‘Kestrel’. Bold combinations of materials and rhythmic alternations of reliefs and counter-reliefs resulted in an optical effect of movement and a new plastic language. The subjects of these aesthetically balanced works were not tied to any specific time period as well as devoid of any signs of social realism that were then dominant in the artistic world.

Even before the ‘Tree of Life’ and ‘Kestrel’, Alla Horska and Viktor Zaretskyi, due to their active civic stance, were marked by the Soviet authorities as ‘Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists’. This status became an actual stigma for social and cultural figures in the USSR who dared to diverge from the party doctrine. Horska’s and Zaretskyi’s artworks were routinely destroyed, and most of Alla Horska’s works in Kyiv were lost forever. Since Horska was a prominent Sixtier artist and a human rights defender, the Soviets persecuted and brutally killed her in 1970.

The Soviet authorities also ordered the destruction of her mosaics in Mariupol. However, the locals did not obey and hid the panel behind a brick false wall, effectively preserving this priceless work of art.

Surviving mosaics, paintings, and graphic works by Alla Horska are kept not only in the national art museums in Kyiv and Lviv but also in the Berlin Wall Museum at Checkpoint Charlie. They are also an adornment of the collection of Norton and Nancy Dodge at Rutgers University in the USA, one of the largest collections of Soviet nonconformism in the world. Some of the artworks had also been preserved in Mariupol until the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Endless shelling and bombing by Russian troops from the air, sea, and land were ruining and razing the city to the ground day by day. As a result, the unique mosaic panels by the Ukrainian monumentalists have been completely destroyed.

The city that once held memories has now turned into a memory itself.