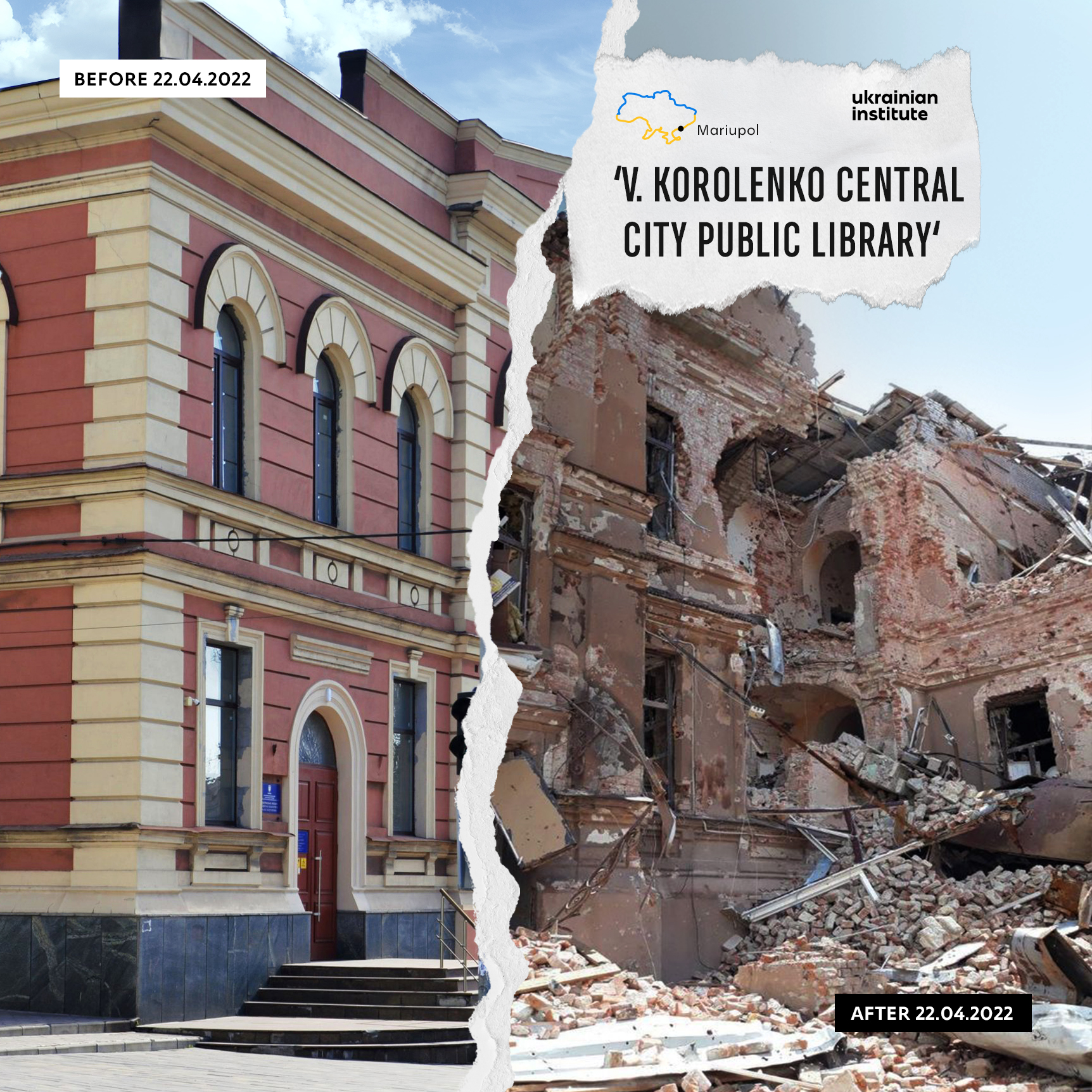

The manor of Mariupol City Council’s mayor, having more than 150 years of history behind. Its architecture incorporated elements of the Stalinist Empire, Neoclassicism, and Baroque.

Mariupol saw rapid growth in the second half of the 19th century. Not everyone could afford a house on the main street of this seaside town. In the late 19th century, Illia Yuriev purchased a house in the city centre, a two-storey residential building on Katerynynska Street (today, 40 Myru Street). He was a respected member of the community, a lawyer at the district court, the City Duma’s chairman since March 1907, the district school board’s member, and a trustee of the city elementary school named after Metropolitan Ignatius.

Yuriev rented out the ground floor of his estate, and the editorial office of one of the city’s first periodicals, ‘Mariupol Reference Leaflet,’ started operating there. This editorial office was replaced in 1912 by ‘The 20th Century’ cinema hall. However, the Bolsheviks shut it down in the 1920s as soon as they took over Ukraine. They nationalised Yuriev’s house, first opening an orphanage there before turning it into a branch of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs of the USSR, a ruthless repressive tool of the Soviet government.

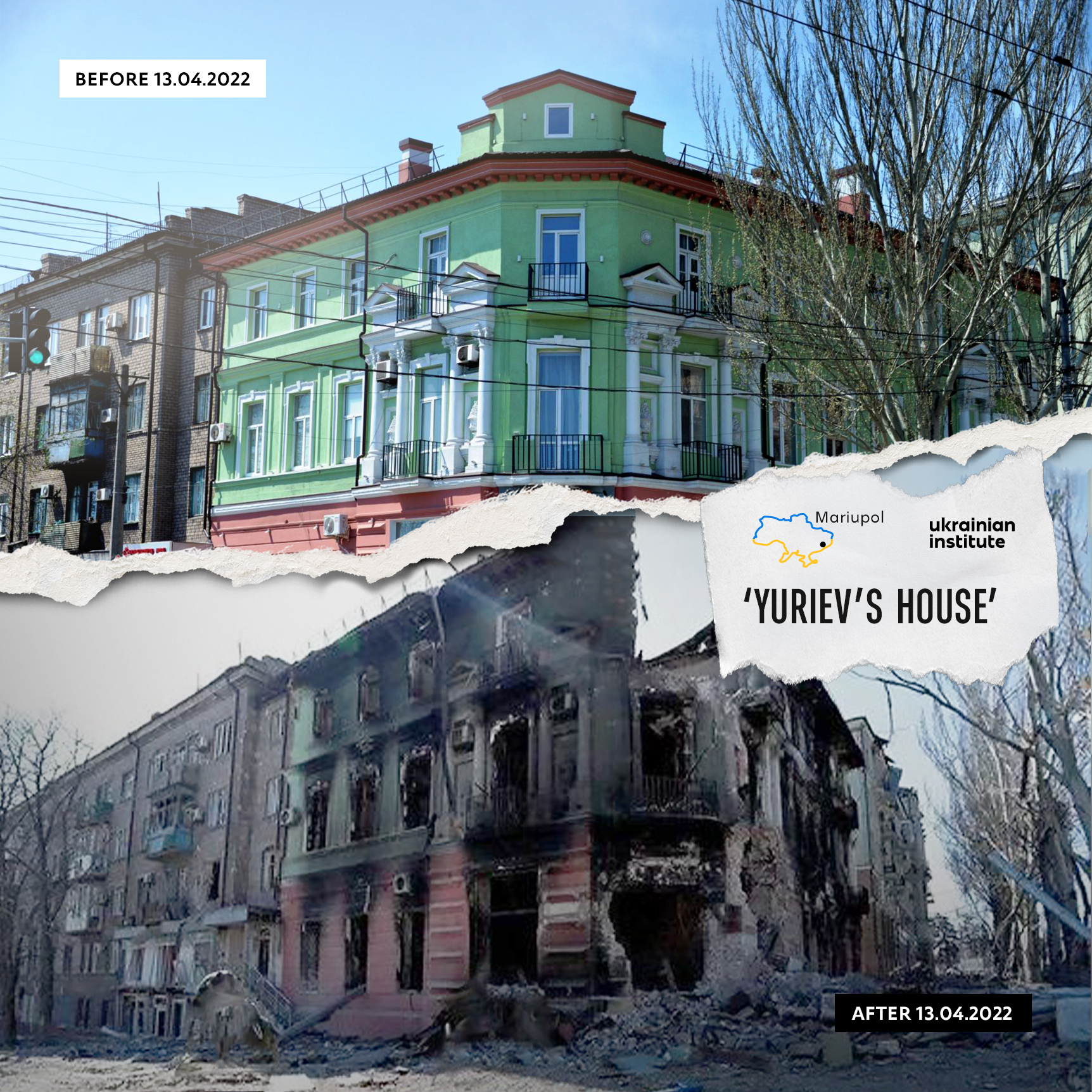

The Nazis established the Gestapo headquarters here during World War II. They set fire to the lawyer’s former estate during the retreat. But after a few years, it was restored, giving the structure a more contemporary appearance. The house was expanded with a third floor, and its architecture incorporated elements of the Stalinist Empire, Neoclassicism, and Baroque.

During the Soviet era, the ground floor served as a shoe store, and the upper floors were used for administrative purposes. Following Ukraine’s independence, Yuriev’s house became residential again. A forced migrant from Donetsk who had served in the military during Russia’s war in the Donbas in 2014 opened a coffee shop with a library on the ground floor. Thanks to a grant from the UN program for business development and the significant support of many Ukrainians, the idea was put into action. Mariupol residents enjoyed coffee and observed city life in this atmospheric setting.

The city view from the 150-year-old monument’s windows has significantly darkened since the start of Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine at the end of February 2022. Mariupol, once a thriving city, was now totally destroyed. Russian shelling mutilated the facades, roof, and interiors of Yuriev’s house.

The site that once held the memories of generations of Mariupol residents from various eras may now turn into a memory itself.